[vc_row njt-role=”people-in-the-roles” njt-role-user-roles=”administrator,editor,author,armember”][vc_column][vc_column_text]

The Korea’s conquest of the luxury market is largely based on the soft power promised by Hallyu. A wave of Korean cultural products, including music, TV series and, above all, Idols, which has a global impact because of its visceral optimism.

As we saw in our previous episode, Hallyu’s strength lies not only in its ability to showcase the local creative economy. If K-pop, K-drama and Manhwas (Korean comics) are so successful, it’s because they are vehicles for values shared by the greatest number of people.

This is a decisive factor in luxury brands’ choice of ambassadors from these extended universes.

Korean entertainment takes on the world

Two industries have been particularly prolific in spreading Korean culture and values: TV series (K-drama) and music (K-pop).

Less than 15 years after the theorization of the production method, TV series swept across Asia and the Middle East in the late 1990s.

However, the Korean wave (Hallyu) didn’t conquer the West until the mid-2000s.

By 2015, Korean soft power had already reached the USA, although it wasn’t until 2019 that K-pop was no longer considered a niche musical genre.

Girls Generation, BTS, BlackPink, Aespa, New Jeans… a whole flock of groups are releasing hit after hit, surrounded by the best and served by over-trained performers.

Behind this frenzied production of tried-and-tested groups are four entertainment majors: SM Entertainment (Girls Generation), considered the pioneer of K-pop production and distribution methods; YG Entertainment (BlackPink); JYP Entertainment; and HYBE, formerly Big Hit Entertainment, which will go public in 2021 (BTS). For its part, SG Entertainment is a pioneer in luxury brand sponsorship.

Formerly known as Big Hit Entertainment, it was one of South Korea’s fortieth most valuable companies on the stock market, with a value of 7.4 billion euros at the end of 2020.

The latter has more than gained a foothold in what appears to be the new target market for K-pop productions: the USA.

In 2021, Big Hit Entertainment, now HYBE, bought Ithaca Holdings, the studio that manages artists such as Justin Bieber and Ariana Grande, for around $1 billion. Last February, it acquired Quality Control Music, the Atlanta rap label. These deals have enabled HYBE to more than double its sales, three quarters of which now come from outside South Korea.

Contrary to popular belief, it wasn’t the singer Psy and his song Gangnam Style, written in Korean and released in 2012, that propelled K-pop onto the international scene. But it was the breakthrough in the American charts of the group BTS thanks to their use of English that was decisive.

Another sign of this viral gloom is the rewriting of certain melodies in line with these trends. For their 2022 cover of Stevie Wonder’s 1984 hit “I Just Call To Say I Love You”, Neiked, Anne-Marie and Latto renamed their song “I Just Call To Say I Hate You”.

On the other hand, K-pop music titles such as BTS, New Jeans, Fifty Fifty and Black Pink offer rather flowery songs about love with a big L, with a catchy rhythm and a lot of snappy lyrics.

Unlike American productions, here there’s no violence, “F words” or sexualization of interpersonal relationships. In other words, consensual lyrics that make these musical productions just as well suited to the Asian market as they are to the Gulf states. The latter – particularly the Emirates and Saudi Arabia – are very fond of Korean series.

If the phenomenon conquered Arab countries between the late 1990s and early 2000s, it’s thanks to the strong similarities between Muslim and Korean culture. These include the preponderance of family ties and the relationship between sexuality and sensuality.

Not only do K-dramas have no nudity scenes, but it’s not uncommon to have to wait until episode 8 to see a first kiss.

Not to mention the fact that K-drama emphasizes the characters’ backstories and the art of courtship, all paced at a rate of one season and two one-hour episodes aired per week on two consecutive days. It’s enough to whet the appetite for everything from fashion accessories to cosmetics and even plastic surgery.

It’s a detail that hasn’t escaped the attention of the luxury goods industry, which sees many similarities in values.

Luxury, the country’s future big brother?

In Korea, there’s an affectionate expression used by girls, pronounced, as much to evoke an older friend, as a companion: Oppa (오빠) which can be translated as “big brother”. The same expression exists for girls to call their older friends: Eonni (언니).

It turns out that in its perfectionism, community spirit and transparency, Kpop has far more in common with post-modern luxury than one might suspect.

This community of interests is reflected in the presentation of SG Entertainment by its CEO, Thomas Sommer.

“We are joining two of the most promising industries in today’s economy. On the one hand, there’s entertainment, via the creation of idols, role-models that people will follow. On the other, there’s luxury, which is the materialization of passion, the life drive and the desire for ascendancy, i.e. the will to improve one’s living condition.”

Excellence in execution

The Land of the Morning Calm is known for its cult of perfection, which is reflected in both its singing performances and its acrobatic choreography, which would not be denied by Michael Jackson and his Jackson 5 band. All of which echoes the excellence of execution expected of a luxury product or service.

Unlike the Western model, where labels, producers and agencies look for seasoned professionals in their disciplines to take them to the top, in K-pop, the aim is to select future stars on the basis of their physical appearance and, above all, to detect their potential. And this from an early age, since some can start training as early as 15. The studio takes care of the rest. It took six years to create a group like BlackPink, with drastic training in singing, rapping, dancing, acting, posture and communication. Not to mention the fact that in K-pop productions, each member’s skills are complementary.

As Vincenzo Cicchelli and Sylvie Octobre describe in their book K-pop, soft power et culture globale, for every 100,000 teenagers auditioned to join a K-pop group, 1% will undergo training and only 0.1% will make a career.

As a result, South Korea has as many pop artists as the USA, albeit with a smaller population (51 million VS 330 million inhabitants). The price of fame: the chosen few lose all freedom and privacy, to the point where fans can follow them via social networks, from their concerts to their…dormitory villa. All band members have to live in shared apartments.

And that’s not all: the quest for perfection extends to the cult of the body. South Korea ranks third in the world in terms of annual cosmetic surgery operations, behind the United States and Brazil. There are no fewer than 1,300 specialized clinics in the country.

Another characteristic of the Korean market is the need to combine beauty and kindness.

As Sylvie Octobre explains, “In Korea, bad boys and bad girls don’t exist. That doesn’t mean there can’t be strong women, like BlackPink. The reason is simple: over there, if an actor or singer is caught drunk, using drugs or having illicit sex (prostitutes or adulterers), his or her career is shattered.” Like Marilyn Monroe or Brigitte Bardot at the start of her career, the star must also remain available and not be in a relationship, unless the other half has been designated and approved by the producers.

Thomas Sommer (SG Entertainment) recalls how the Idol phenomenon works in Korea: “We’re back to the Confucian model of exemplarity: Koreans function by mimicry, they don’t think in terms of abstract moral values. It all boils down to a simple equation: This idol is famous and reputable, so she’s a good person, and I’m going to do what she does.”

The result is an image in which all behavior is perfectly “controlled”. Thus, both BlackPink and Girl Generation present “clean beauty”, devoid of asperity.

The risk of a slip-up or any behavior deemed deviant, as in the case of Chinese influencers Viya and Austin Li Jiaqi or film star Fan Bingbing, is therefore virtually impossible.

However, as in the West, a group can be disbanded or put on hiatus to allow certain members to pursue their solo careers for a time, before reconstituting themselves or not. Studio Spire Entertainment has made this its trademark. It has set up a group made up exclusively of 11 ex-K-pop members: Spire and The Diamonds.

In the fourth episode, we’ll look at the main reason why luxury brands are so keen on idols: to reduce the cost of customer acquisition by appealing directly to the highly engaged community of all these artists.

Read also > [INVESTIGATION] South Korea: When Western luxury woos K-pop (Part 2/5)

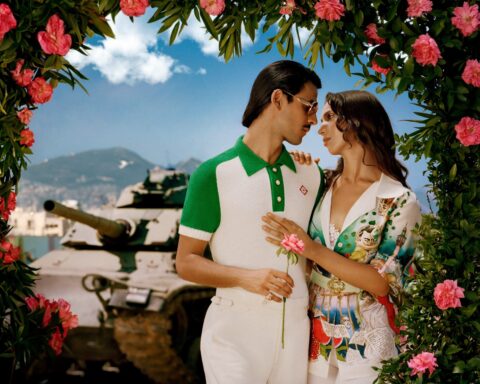

Featured photo : © Press [/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row njt-role=”not-logged-in”][vc_column][vc_column_text]

The Korea’s conquest of the luxury market is largely based on the soft power promised by Hallyu. A wave of Korean cultural products, including music, TV series and, above all, Idols, which has a global impact because of its visceral optimism.

As we saw in our previous episode, Hallyu’s strength lies not only in its ability to showcase the local creative economy. If K-pop, K-drama and Manhwas (Korean comics) are so successful, it’s because they are vehicles for values shared by the greatest number of people.

This is a decisive factor in luxury brands’ choice of ambassadors from these extended universes.

Korean entertainment takes on the world

Two industries have been particularly prolific in spreading Korean culture and values: TV series (K-drama) and music (K-pop).

Less than 15 years after the theorization of the production method, TV series swept across Asia and the Middle East in the late 1990s.

However, the Korean wave (Hallyu) didn’t conquer the West until the mid-2000s.

By 2015, Korean soft power had already reached the USA, although it wasn’t until 2019 that K-pop was no longer considered a niche musical genre.

Girls Generation, BTS, BlackPink, Aespa, New Jeans… a whole flock of groups are releasing hit after hit, surrounded by the best and served by over-trained performers.

Behind this frenzied production of tried-and-tested groups are four entertainment majors: SM Entertainment (Girls Generation), considered the pioneer of K-pop production and distribution methods; YG Entertainment (BlackPink); JYP Entertainment; and HYBE, formerly Big Hit Entertainment, which will go public in 2021 (BTS). For its part, SG Entertainment is a pioneer in luxury brand sponsorship.

Formerly known as Big Hit Entertainment, it was one of South Korea’s fortieth most valuable companies on the stock market, with a value of 7.4 billion euros at the end of 2020.

The latter has more than gained a foothold in what appears to be the new target market for K-pop productions: the USA.

In 2021, Big Hit Entertainment, now HYBE, bought Ithaca Holdings, the studio that manages artists such as Justin Bieber and Ariana Grande, for around $1 billion. Last February, it acquired Quality Control Music, the Atlanta rap label. These deals have enabled HYBE to more than double its sales, three quarters of which now come from outside South Korea.

Contrary to popular belief, it wasn’t the singer Psy and his song Gangnam Style, written in Korean and released in 2012, that propelled K-pop onto the international scene. But it was the breakthrough in the American charts of the group BTS thanks to their use of English that was decisive.

Another sign of this viral gloom is the rewriting of certain melodies in line with these trends. For their 2022 cover of Stevie Wonder’s 1984 hit “I Just Call To Say I Love You”, Neiked, Anne-Marie and Latto renamed their song “I Just Call To Say I Hate You”.

On the other hand, K-pop music titles such as BTS, New Jeans, Fifty Fifty and Black Pink offer rather flowery songs about love with a big L, with a catchy rhythm and a lot of snappy lyrics.

Unlike American productions, here there’s no violence, “F words” or sexualization of interpersonal relationships. In other words, consensual lyrics that make these musical productions just as well suited to the Asian market as they are to the Gulf states. The latter – particularly the Emirates and Saudi Arabia – are very fond of Korean series.

[…][/vc_column_text][vc_cta h2=”This article is reserved for subscribers.” h2_font_container=”tag:h2|font_size:16|text_align:left” h2_use_theme_fonts=”yes” h4=”Subscribe now !” h4_font_container=”tag:h2|font_size:32|text_align:left|line_height:bas” h4_use_theme_fonts=”yes” txt_align=”center” color=”black” add_button=”right” btn_title=”I SUBSCRIBE !” btn_color=”danger” btn_size=”lg” btn_align=”center” use_custom_fonts_h2=”true” use_custom_fonts_h4=”true” btn_button_block=”true” btn_custom_onclick=”true” btn_link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fluxus-plus.com%2Fen%2Fsubscriptions-and-newsletter-special-offer-valid-until-september-30-2020-2-2%2F”]Get unlimited access to all articles and live a new reading experience, preview contents, exclusive newsletters…

Already have an account ? Please log in.

[/vc_cta][vc_column_text]Featured photo : © Press[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row njt-role=”people-in-the-roles” njt-role-user-roles=”subscriber,customer”][vc_column][vc_column_text]

The Korea’s conquest of the luxury market is largely based on the soft power promised by Hallyu. A wave of Korean cultural products, including music, TV series and, above all, Idols, which has a global impact because of its visceral optimism.

As we saw in our previous episode, Hallyu’s strength lies not only in its ability to showcase the local creative economy. If K-pop, K-drama and Manhwas (Korean comics) are so successful, it’s because they are vehicles for values shared by the greatest number of people.

This is a decisive factor in luxury brands’ choice of ambassadors from these extended universes.

Korean entertainment takes on the world

Two industries have been particularly prolific in spreading Korean culture and values: TV series (K-drama) and music (K-pop).

Less than 15 years after the theorization of the production method, TV series swept across Asia and the Middle East in the late 1990s.

However, the Korean wave (Hallyu) didn’t conquer the West until the mid-2000s.

By 2015, Korean soft power had already reached the USA, although it wasn’t until 2019 that K-pop was no longer considered a niche musical genre.

Girls Generation, BTS, BlackPink, Aespa, New Jeans… a whole flock of groups are releasing hit after hit, surrounded by the best and served by over-trained performers.

Behind this frenzied production of tried-and-tested groups are four entertainment majors: SM Entertainment (Girls Generation), considered the pioneer of K-pop production and distribution methods; YG Entertainment (BlackPink); JYP Entertainment; and HYBE, formerly Big Hit Entertainment, which will go public in 2021 (BTS). For its part, SG Entertainment is a pioneer in luxury brand sponsorship.

Formerly known as Big Hit Entertainment, it was one of South Korea’s fortieth most valuable companies on the stock market, with a value of 7.4 billion euros at the end of 2020.

The latter has more than gained a foothold in what appears to be the new target market for K-pop productions: the USA.

In 2021, Big Hit Entertainment, now HYBE, bought Ithaca Holdings, the studio that manages artists such as Justin Bieber and Ariana Grande, for around $1 billion. Last February, it acquired Quality Control Music, the Atlanta rap label. These deals have enabled HYBE to more than double its sales, three quarters of which now come from outside South Korea.

Contrary to popular belief, it wasn’t the singer Psy and his song Gangnam Style, written in Korean and released in 2012, that propelled K-pop onto the international scene. But it was the breakthrough in the American charts of the group BTS thanks to their use of English that was decisive.

Another sign of this viral gloom is the rewriting of certain melodies in line with these trends. For their 2022 cover of Stevie Wonder’s 1984 hit “I Just Call To Say I Love You”, Neiked, Anne-Marie and Latto renamed their song “I Just Call To Say I Hate You”.

On the other hand, K-pop music titles such as BTS, New Jeans, Fifty Fifty and Black Pink offer rather flowery songs about love with a big L, with a catchy rhythm and a lot of snappy lyrics.

Unlike American productions, here there’s no violence, “F words” or sexualization of interpersonal relationships. In other words, consensual lyrics that make these musical productions just as well suited to the Asian market as they are to the Gulf states. The latter – particularly the Emirates and Saudi Arabia – are very fond of Korean series.

[…][/vc_column_text][vc_cta h2=”This article is reserved for subscribers.” h2_font_container=”tag:h2|font_size:16|text_align:left” h2_use_theme_fonts=”yes” h4=”Subscribe now !” h4_font_container=”tag:h2|font_size:32|text_align:left|line_height:bas” h4_use_theme_fonts=”yes” txt_align=”center” color=”black” add_button=”right” btn_title=”I SUBSCRIBE !” btn_color=”danger” btn_size=”lg” btn_align=”center” use_custom_fonts_h2=”true” use_custom_fonts_h4=”true” btn_button_block=”true” btn_custom_onclick=”true” btn_link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fluxus-plus.com%2Fen%2Fsubscriptions-and-newsletter-special-offer-valid-until-september-30-2020-2-2%2F”]Get unlimited access to all articles and live a new reading experience, preview contents, exclusive newsletters…

Already have an account ? Please log in.

[/vc_cta][vc_column_text]Featured photo : © Press [/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]