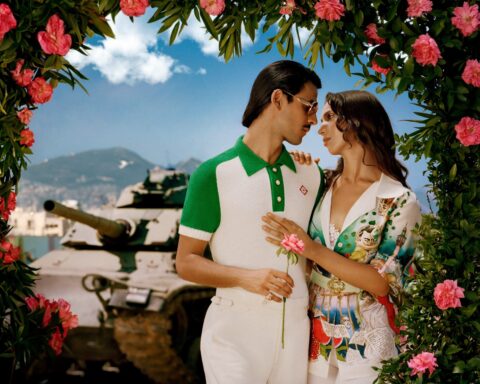

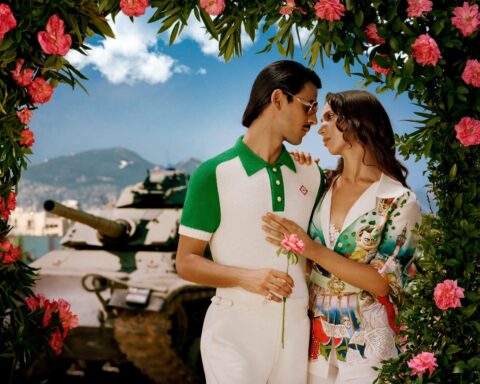

It’s polo season in Thailand and teams of jodhpur-clad Argentines and monied Asians gallop onto the flawless field, as spectators spill from a pavilion — glasses of champagne in hand — for the final chukka.

© 2019 Chonburi (Thailand) (AFP)

The “Sport of Kings” is undergoing an unlikely renewal in Thailand, one of the world’s most unequal countries, which goes to the polls on March 24 with the widening wealth gap in sharp focus.

Thailand boasts 50 billionaires, according to the latest rich list published by China-based researchers at the Hurun Report, the ninth-most in the world and more than France, Japan and Singapore.

Some of that cash paid for the play at a recent charity event at the Thai Polo & Equestrian Club, an unexpected oasis of immaculate lawns, wood-panelled changing rooms and stables a stone’s throw from the raucous “Sin City” of Pattaya.

“Is polo elitist? Yes, you cannot deny it is a very elite sport,” says Nunthinee Tanner, the club’s convivial co-founder and doyenne of the Thai equestrian scene.

“A small group play across the world because it’s very expensive and takes a lot of practice.”

As she speaks, Thai “HiSo” (High Society) women in striking millinery and high heels pick their way over the soft turf.

Laughter peals from the Veuve Clicquot tent where men in seersuckers and pink trousers have encamped for the day.

“It’s a sport of CEOs and royalty,” Nunthinee explains.

On cue, billionaire Harald Link — a German-born naturalised Thai businessman and philanthropist who co-owns the club — leads the home team onto the field, mallet in hand.

Other team patrons include Brian Xu, the Shanghai-based head of the world’s biggest pencil-making firms, while Sultan Abdullah was a last-minute no-show after his sudden elevation to the Malaysian throne.

Invented by Persian warriors and codified by British imperialists, polo has long found a home in Thailand, a kingdom where royalty, wealth and elite networks are cross-hatched into the social fabric.

Most teams are top-loaded with Argentines who command huge salaries, stumped up by patrons to play alongside the best.

Thai duty free tycoon Vichai Srivaddhanaprabha was among the sport’s biggest spenders.

He died last year in a helicopter crash outside his beloved Leicester City football club in Britain, leaving an estimated $5.8 billion fortune to his heir.

– Patronage pays –

Wealth is a hot button election issue ahead of polls this month after nearly five years of junta rule.

Party leaders from across the political spectrum wield promises of raising incomes and addressing inequality.

“The top 20 percent own 80 percent of wealth,” Kobsak Pootrakool, spokesman for the junta-aligned Phalang Pracharat party and the current government’s inequality tsar told AFP.

“The World Bank says we are a miracle of Asia… but when you look closely we perform so badly in terms of inequality.”

But the fine pre-poll words are not expected to translate into wealth redistribution.

The army has seized power a dozen times in under 100 years.

It has done so with the support of much of the Bangkok-based elite, who underpin the kingdom’s sharp hierarchy and bristle at economic and political challenges from below.

The nation’s monarchy is among the world’s richest.

Cash also cascades down family businesses clans, whose monopolies are inoculated against competition by friends and family in politics and generous tax breaks, while generals sit on company boards.

“Big capital and the military are in the same bed,” Thanathorn Juangroongruangkit, leader of the upstart anti-junta Future Forward Party and the son of one of the country’s 50 billionaires, told AFP.

“Inequality won’t be solved” unless that clot of power and money is removed, he says, warning of a threat to stability by a wealth gap described by a Credit Suisse study as the widest in the world.

The pinch of rising living costs, debt and dipping farm incomes is being felt more keenly under the rule of unelected generals.

Over 14.5 million Thais qualify for welfare, the majority earning less than $1,000 a year.

Yet the widespread griping has not spilled into unrest, with many Thais focused on voting after an eight-year hiatus and then looking towards the next government to give the grassroots economy a lift.

Inequality is also stunting Thailand’s hopes of moving to “advanced economy” status, the World Bank said in a recent report, blaming poor state education for trapping the majority on a treadmill of low-paid, low-skilled jobs.

That is booking in trouble for the future, experts say, with automation poised to cut further into the low-skilled labour force.

On the sidelines of a recent political rally, Nirut Saensri was sanguine about his lot in life as he crushed empty plastic bottles for recycling for a few dollars a day.

“I’m poor and can’t always get enough to eat,” the thin, crumpled 47-year-old said. “But I don’t need luxury and I’m not envious of the rich.”

– Show me the money –

Across town, Bangkok’s HiSo culture is flourishing.

Chi-chi neighbourhoods are decorated by nightly celebrity parties, amplified by social media and attended to by an armada of drivers, assistants and concierges.

Sales of luxury condos and supercars are surging — Aston Martin says it flogged a record 250, each for over $475,000, in Bangkok last year.

But the showy wealth of the newly-minted has also opened up a divide at the top.

“To me real ‘High Society’ is aristocracy and old money,” socialite and businesswoman Khun Nu Lek told AFP at a flower show at her family’s vast gardens in downtown Bangkok.

Lek — full name Naphaporn Bodiratnangkura — is a descendant of the Nai Lerts, a family favoured by Thai royalty for generations for their business acumen.

She acknowledges the “rich are getting richer” but says the kingdom’s yawning wealth gap is worrying.

“I also want to see the poor getting richer. That’s not happening,” she adds.

burs-apj/gle/tom